This blog post appeared originally in a tweet thread here: https://twitter.com/PlavchanPeter/status/1451262732800561166

This article about the early days of astronomers' reactions to the launch of starlink haunts me, and the time & leadership lost that resulted. As the Director of the Rubin Observatory Tony Tyson himself said "All was happy and nice with our heads buried underneath the sand.”

As I read yet another article on the battle for the night sky, it seems like astronomy leadership made some key missteps. Now, hindsight is "2020", we've been living through a pandemic, but here's my thoughts on how we failed to react nimbly to this disruptive change:

First, leadership thought too narrowly. Tyson fixated on 7th magnitude for darkening the satellites. Why? The satellite brightness upper limit was driven by how the Rubin Observatory, with it's ~$0.5B US taxpayer cost & personnel could mitigate satellite trails to "denoise" science images, which "by gosh ... pure coincidence" (put Tyson) also put the satellites beyond the gaze of the unaided eye view of the natural beauty of the night sky. But this narrow focus on Rubin Observatory by Tyson at worst ignored and at best minimized the impact on... every other telescope on the planet, including smaller professional telescopes without the resources to procure and implement imaging de-noising of satellite trails, such as our 0.8m at George Mason Observatory. This short-sightedness extended to amateur telescopes, binoculars, and sidereal-tracking mounted DSLR cameras for amateur astronomers, wide-field astro-photography, education and outreach sharing the beautiful splendor of the night sky just beyond the gaze of the unaided eye. This lack of vision extended to radio astronomy already inundated with wifi and cell towers corralled to radio quiet "zones" such as the US taxpayer funded Green Bank Observatory and Owen's Valley, now facing an impenetrable source of radio light pollution.

We've seen this before with the pollution of city lights and the escape of astronomers to remote dark sky sites, to children who grow up in urban areas and reach adulthood never once gazing upon the wonders of the Milky Way in all its splendor. No, leadership thought too narrowly, ignoring the impacts beyond the light pollution, such as the aluminum pollution of the upper Earth atmosphere, aka the space industries giant backyard trash fire, the potential for the Kessler syndrome. We ignored the global implications from our US-centric elitism, the lack of regulation in space, how a single private US billionaire can change the night sky for a planet of billions of humans, AND quadrillions of other life forms that make use of the night sky for everything from navigation for dung beetles to reproduction with the lunar cycle for fish.

Second, leadership reacted too narrowly. As captured in the lede article of this thread, Tony Tyson tried to solve this problem "engineer to engineer" and "wanted to avoid public conflict". In the early days of Starlink, I wondered where the eff was the Rubin Observatory. There was no public announcement; no public outcry. Now I know; the VRO tried to solve a grand-challenge big-science problem on their own, a recipe for disaster. Pandora's rocket had already launched; it was too late to expect a solitary small-scale, narrow-focus effort to bring the starlink genie back down to Earth. It was also effin' elitist to assume Rubin Observatory engineers alone could solve all the concerns above. This was incredibly shortsighted and insulting to the rest of the professional astronomy community, amateur astronomers, and the rest of the planet.

So, while Rubin Obs was off working in isolation (a private corporation by the way), what was the leadership of the American Astronomical Society for professional astronomers doing? They wanted "to avoid a confrontation that could damage the SpaceX partnership" and declined legal help. When the NEPA article challenging the pollution effects came out, the AAS leadership was declining multiple offers of legal assistance. And it took a competitor, ViaSat to mount a legal challenge. Are you effing kidding me? No, the AAS and Rubin Obs leadership, with the privilege to be able to get Elon Musk on a phone call, screwed this one up. Big time. “I don’t read the FCC filings for entertainment purposes,” Tyson says. “On balance, my bad.” Exactly.

So the scientists of the American Astronomical Society did what they could in the vacuum of leadership, they formed a committee with collaboration with SpaceX. “Several of us were compared to Neville Chamberlain, for having sold out the astronomical community.”

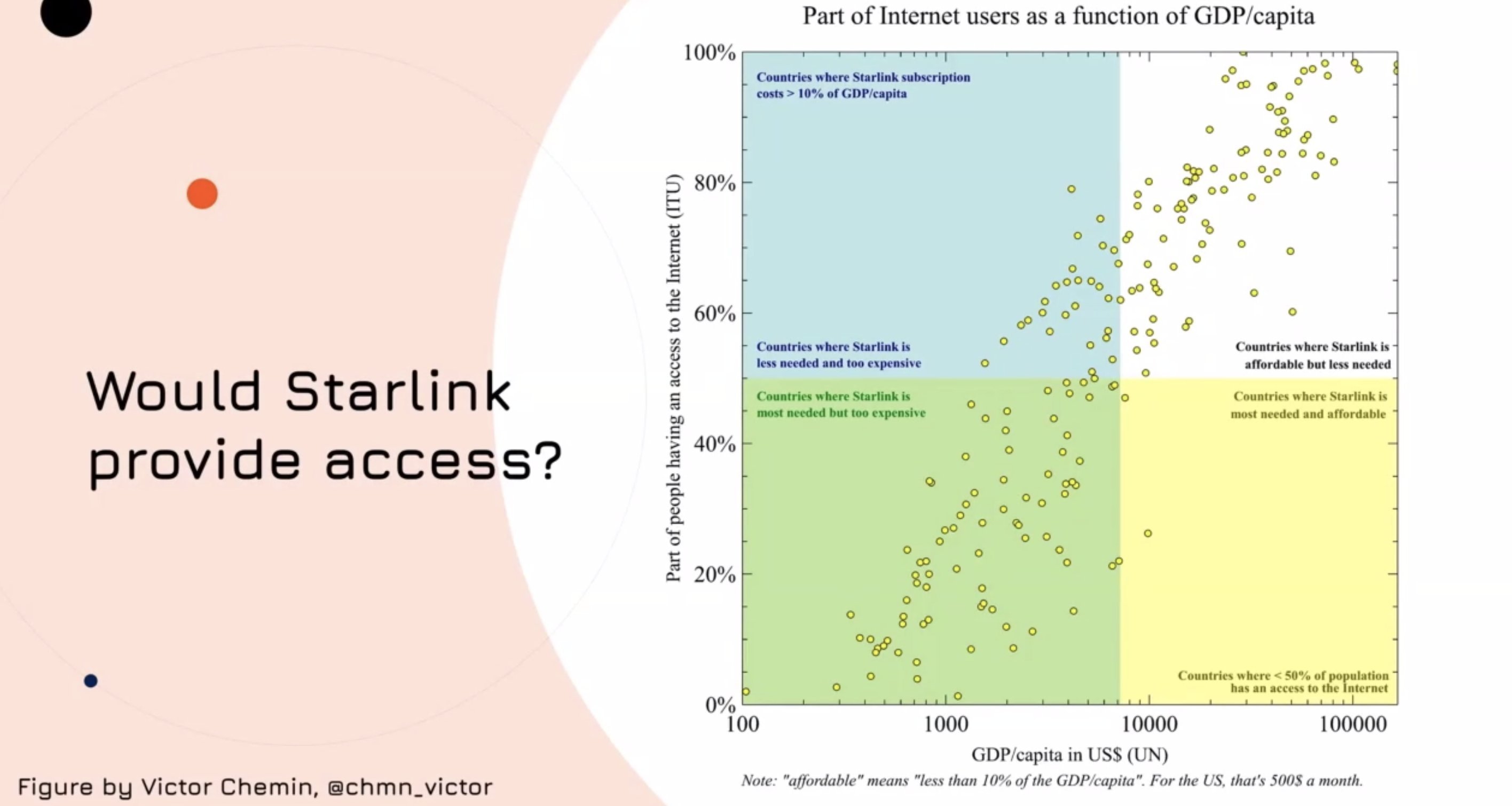

Third, we were then completely oblivious. Sure we attacked the main thesis for a low-latency low-cost global internet service for rural populations worldwide as financial hogwash:

Source: https://twitter.com/alexgagliano/status/1295387477402955777 and slides from Lucianne Walkowicz.

We puzzled at the breeze of approvals from the FCC. But we missed the customer who was there for Starlink since Day 1, even before the first batch of 60 launched on 11/19/2019: the US military. Here's a Reuters article from 10/22/2019 hiding in plain sight of the Air Force partnering with SpaceX.

Then the Army followed in March 2020. It wasn't just about the cost, it was the low latency and the military capabilities. Sure, the role the military may have played in the ease of the FCC approval is pure speculation, but astronomers were oblivious to another consequence of the military applications: every capable nation would want their own satellite network, increasing their number by an order of magnitude. Leadership at the AAS and VRO naively assumed that either the satellite companies would fail like OneWeb, or older examples like Iridium, or 1-2 companies would "win" the race to build them, limiting the total number of satellites on orbit. No, we were oblivious to the idea that all countries would want their own networks for military applications.

A global problem requires global engagement, and here again the US leadership has fallen woefully short. Astronomers are still working from the ground up, albeit too slowly to have an impact. SATCON1 was held in the summer of 2020, but it focused on the scientific impacts on astronomy. Everything else was deferred until SATCON2 in the summer of 2021. Since then, SpaceX managed to launch over 1400 operational satellites in that time. There was no pause, there was no regulation, there were no hearings resulting from the NEPA legal arguments against the pollution of satellite networks. The FCC has continued to approve what SpaceX wants to do, even over the objections of Amazon.

I applied to join one of the four working groups as a director of a 0.8m Observatory, and as geographically proximate to the US policy makers on the Hill, but I was not selected to be included. Frankly, I'm ok with that decision, I had enough going on in my life at the time. SATCON1 and 2 however are grass-roots efforts starting like how environmental movements started in the past - poorly resourced and being bullied around by those in power. Heck, I'm not even sure what the International Astronomical Union is doing, but it's not even making enough of an impact for me to hear anything about it and I'm a professional astronomer.

Frankly, right now what we need is leadership. We need AAS leadership in the US through engagement with the executive branch and Congress.We need international dialog at the UN and peer-to-peer.We need interdisciplinary international regulation of space and space industries. I'm hoping it's not too late. This grand challenge is much bigger than satellite communication networks, and much bigger than astronomy. What we have now is woefully inadequate. Sure, it's not as big of a grand challenge we face as a global society such as climate change, but we've been far too short-sighted about regulating space and space industries during the past two years.

No comments:

Post a Comment